Today is the first day of the 72nd Sydney Film Festival. The festival will run from the 4th to the 15th of June, with the earliest screenings of each day starting at 9AM and the latest ending at midnight. I’ve booked tickets to movies on every day of the festival, and on most days I’ll be watching multiple movies. All-in-all, I’ve booked tickets to 40 movies over the next 12 days.

The first day of any film festival is, like the last day of school, only a “half day” because its Opening Night premiere has to happen at night1. The 72nd Sydney Film Festival’s Opening Night film is Together: a Neon-distributed, Australian-American co-produced, “supernatural body-horror romance” which is the feature film debut of Australian writer-director Michael Shanks starring IRL married couple Alison Brie & Dave Franco, and which premiered to good reviews2 earlier this year in the Midnight section at Sundance. The Opening Night film, along with the Closing Night film and the 12 films competing in the Official Competition, will be screening at The State Theatre: a beautiful, 2034-seat, heritage-listed, Gothic/Italian/Art-Deco-inspired theatre built in the heart of the city — just a few blocks from Town Hall — in 1929. It usually hosts live performances, like plays and concerts, but for the next two weeks it’ll be the “home” of the Sydney Film Festival3.

I won’t be going to the State Theatre tonight. Instead, I’ll be 500m down the road at the Event Cinemas George Street where I’ve booked a double feature of “unrelated movies which have the word ‘end’ in their title”: Happyend at 6:15PM and then It Ends at 8:30PM. However, since I don’t want to catch the train during rush hour, I decide to get into the city a little earlier and make today a triple feature starting with the 3:15PM session of The Phoenician Scheme.

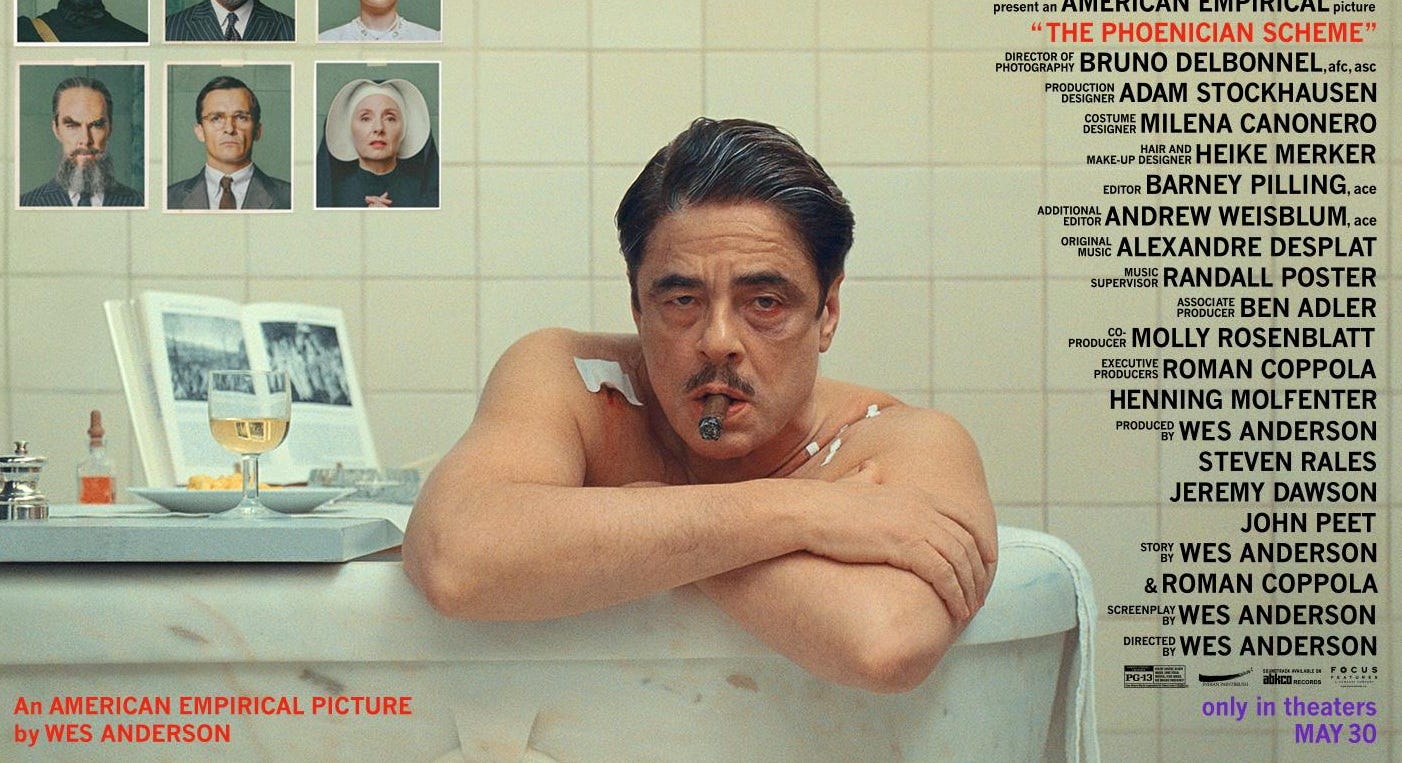

(3:15PM) The Phoenician Scheme

Wealthy businessman, Zsa-Zsa Korda (Benicio Del Toro) appoints his only daughter (Mia Threapleton), a nun, as sole heir to his estate. As Korda embarks on a new enterprise, they soon become the target of scheming tycoons, foreign terrorists and determined assassins.

Director: Wes Anderson

Writers: Wes Anderson & Roman Coppola

Stars: Benicio Del Toro, Mia Threapleton, Michael Cera, Riz Ahmed, Tom Hanks, Bryan Cranston, Mathieu Amalric, Richard Ayoade, Jeffrey Wright, Scarlett Johansson, Benedict Cumberbatch, Rupert Friend, Hope Davis, Bill Murray, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Willem Dafoe, F. Murray Abraham, Stephen Park

I already watched The Phoenician Scheme on the day it came out, May 29th, which was last Thursday. So you might assume I’d loved the movie since I’m rewatching it solo after only 5 days. But I hadn’t loved it.

I’d liked The Phoenician Scheme the first time I watched it.

I’d enjoyed it for all the usual pleasures of any Wes Anderson movie: its All-Star ensemble cast, its pastel diorama production design, its eceletic needle-drops and its hilarious deadpan one-liners. But I’d barely been able to follow the plot, which is been a lot more complicated than most Wes Anderson stories4; let alone contemplate the subtext in its Brechtian performances, its high-cultural references from Magritte to Stravinsky, or its deeper themes examining the relationship between the 3 C’s of Western Civilization: capitalism, colonialism, and Christianity.

But I’m hopeful that it’ll all make sense on the rewatch. For I hadn’t “got” Asteroid City on the first watch either; but on the rewatch it leapt up from S- to 🦄 tier5 to become my #1 Movie of 2023 and my Favourite Wes Anderson movie, and its only risen further up my personal rankings of Every Movie I’ve Ever Watched6 on each subsequent rewatch7. So I’m hoping to have a similar reappraisal of The Phoenician Scheme, as I sit down to rewatch it at 3:15PM on a Wednesday…

…It’s now 5:25PM and I can comfortably say that The Phoenician Scheme is not a movie that needs to be watched twice.

Maybe I need to rewatch it a third time because, to be fair, I did fall asleep in the middle of it for about 10-15 minutes8 — to be specific, I dozed off halfway through the Tom Hanks & Bryan Cranston basketball scene and woke up halfway through the Jeffrey Wright & Matthieu Amalric blood transfusion scene — and maybe that was because I only got 5 hours of sleep last night9, but then again maybe it was just because that stretch of the movie isn’t very interesting?

In the 5 days between watching and rewatching The Phoenician Scheme, I had listened to a podcast interview where Wes Anderson explained how the character of Zsa-Zsa Korda was inspired by his father-in-law, Fouad Malouf, who’d been a Lebanese engineer who’d worked on gigantic construction projects in the Middle East; as well as the lives of Armenian oil tycoon Calouste Gulbenkian10, Italian military-industrialist Giovanni Agnelli, and rival Greek shipping magnates Aristotle Onassis and Stavros Niarchos. I had listened to a different podcast breaking down the De Palma-esque title sequence wherein we watch — in a stationary slow-mo, long-take overhead shot — Zsa-Zsa recuperate from surviving a plane crash by taking a bath while his platoon of servants stream in/out of the bathroom with their movements timed and choreographed, like a ballet, to Stravinsky’s Apollo. I had read an essay on how the movie had filled out Zsa-Zsa’s multi-million-dollar art collection with real masterpieces, instead of reproductions or fake-old originals like most paintings that hang in the background on the fake-walls of movie sets, such as Renoir’s Enfant assis en robe bleue (1889), Margritte’s The Equator (1942), and Juriaen Jacobsz’s The Dog Fight (1678), which they’d borrowed on-loan from museums and private collections throughout Germany11 — for as Zsa-Zsa says in the movie “Never buy good pictures. Buy masterpieces.”

Yet while all this research gave me a greater appreciation for the care and craft that Wes Anderson puts into his work, it didn’t deepen my appreciation for the movie on the rewatch. Yes, I better understood what was happening in each scene; but that didn’t make those scenes more emotionally moving or thematically interesting. Unlike Asteroid City, The Phoenician Scheme doesn’t have layers upon layers of meaning which you can peel back to reveal something new and unexpected on each rewatch. For all the intricacies of its plot, its story is relatively simple12: an infamous father reconnecting with his estranged daughter as they try to pull off “one last job” — which is basically the same story as The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) and The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou (2004).

So The Phoenician Scheme is narratively more like Wes Anderson’s earlier films despite aesthetically being the peak of the “pastel diorama” aesthetic of his later films. Some might say this makes it redundant or repetitive in his filmography; but I think that makes it an interesting transitional work, if still a “minor” work, as a master filmmaker remaking their juvenilia with the expertise of age…but without the fire of youth — like Ozu’s Floating Weeds (1959)13 or Michael Haneke’s Funny Games (2007)14 or Ridley Scott’s Gladiator 2 (2024). But the value The Phoenician Scheme isn’t wholly nostalgic, it adds one new element to the Wes Anderson playset that we’ve never seen done better in any of his other movies: violence.

Violence has always been present in Wes Anderson movies. It’s easy to forget that his debut film wasn’t Rushmore, but Bottle Rocket (1996) — a post-Tarantino neo-noir heist comedy which climaxes in a (comically bumbling but still violent) shoot out. Then there’s the scissor stabbing in Moonrise Kingdom (2012), the serial killing Willem Dafoe in The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), and the “I bite” dogfights in Isle of Dogs (2018). But while these action sequences may have been narratively brutal, and sometimes even fatal, they passed by quickly and were visually more suggestive than explicit — they could’ve passed the censors under the Hayes Code. None of them were as bloody as the opening sequence of this movie; which involves a plane crash, a disembowelment, and an exploding torso — with the J-horror blood splatter staining Wes Anderson’s otherwise immaculate dollhouse world to immediately shock audiences who came in expecting the twee comforts of the #wesanderson TikTok meme. Nor were they as manically unhinged as its climatic chase/fight scene; which involves chemical weapons, suicide-by-grenade, and Benedict Cumberbatch ripping a ladder in half with his barehands; and which is shot with frenetic handheld camerawork that breaks Wes Anderson’s usual slow, steadycam framing.

But although The Phoenician Scheme’s climatic chase/fight scene is very violent, and sometimes even scary, it’s still very funny: Benecio Del Toro and Benedict Cumberbatch duelling each other with lamps is great slapstick comedy! For although The Phoenician Scheme didn’t get better for me on the rewatch, it also didn’t get worse — which isn’t always the case for action comedies, since a middling joke or generic action scene isn’t as funny or thrilling when you already know the punchline or the surprise death. But The Phoenician Scheme has great jokes, from the slapstick of Tom Hanks and Bryan Cranston’s ridiculous 1950s basketball shots to the absurdism of Michael Cera’s ridiculous Norweigan accent15 to Benecio Del Toro’s deadpan delivery of all his oneliners — the most quotable of which include:

“Myself, I feel very safe.” — which he says everytime he barely survives an assasination attempt.

“Help yourself to a grenade!”

“I don’t need human rights.”16

The Phoenician Scheme is not one of Wes Anderson’s best movies17: it’s definitely a step backwards from the masterpiece that is Asteroid City, but hopefully he’s stepping backwards to take a stepback 3 and his next movie will be a Tyrese Haliburton buzzer-beater. For while this movie won’t win Wes Anderson any new fans — if you’re not into his uniquely perculiar style then you never will be because by now it’s clear that he’s never going to change his style — I find it admirable to watch a veteran director, now almost 30 years into his career, double-down on his uniquely perculiar style in a way that should satisfy his existing fanbase18 while still allowing for experimentation (in this case with the introduction of bloody violence). And unlike other aging master filmmakers with unmistakable signature styles, such as Pedro Almodovar or Quentin Tarantino, both of whom are filmmakers I love, his work has yet to descend into nostalgic navel-gazing19 or self-referential movies-about-movies20. Despite all of Wes Anderson’s movies taking place in their own whimsical, candy-coloured alternate universe and none of them having been set in the present-day since The Darjeeling Limited; his movies are nonetheless surprisingly topical and even politically urgent, if in an obtuse way. The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), which was about trying to live luxuriously while blissfully unaware of the rising tide of fascism, dropped only a few years before Trump was elected; and then Isle of Dogs (2018), which was about innocent creatures being deported by a corrupt government who scapegoated them for spreading a (fake) disease, dropped midway through his presidency and only a few years before the start of COVID21. The French Dispatch (2021) was a love-letter to journalism which came out at a time when all journalism was under threat22, by fake news and fascist governments and social media aggregators, and Asteroid City came out in the summer of Barbie and Oppenheimer, where it flew under the radar despite basically being Barbenheimer23 in one movie! And now The Phoenician Scheme, which opens with a plane crash24 and is about war profiteers of the Western World fighting over control of the Middle East, drops at the same time as The Rehearsal Season 2 and Israel bombing Iran (with the implicit backing of the USA)?

At Cannes it was announced that Wes Anderson, his BFF co-writer Roman Coppola, and new friend Richard Ayoade25 were already at work on the script of his next movie, which has so far only been described as “dark”. I wonder if, doubling-down on his experiments with violence in this movie, Wes Anderson’s next movie might be his war movie? I’d be fascinated to see his take on Barry Lyndon (1975) or Lawrence of Arabia (1962) or Inglorious Basterds (2010), or the movie adaptation of Max Fischer’s Vietnam epic Heaven and Hell from Rushmore? But I’m worried that Wes Anderson making a war movie would be a “recession indicator” for WW3.

Grade = S (9.5/10)

(5:25 — 6:15 PM) INTERMISSION

I have 50 minutes to kill before my next movie. I think about walking up a few blocks to Kinokuniya, which is the largest bookshop in Sydney and open until 7PM; but it’s a 10 minute walk, so 20 minutes there and back, which means I’d only have 30 minutes to browse and then get dinner. So I decide to just enjoy my dinner instead, take the time to chew. I consider eating at the Hungry Jacks26 in front of the cinema, but I’m trying to eat healthier. I’ve been spending $200 on WeGovy each month since the start of the year and it feels like I’m just setting that money on fire if I don’t lose any weight in a month because I’m eating junk food. So instead, I walk across the road to the Hero Sushi where I eat 4 plates of nigiri off the conveyor belt.

(6:15 PM) Happyend

Set in near-future Tokyo, two best friends are about to graduate high school, white threats of an earthquake looms. One night, they pull a prank on their principal, leading to a surveillance system being installed. They respond in contrasting ways.

Writer-Director: Neo Sora

Starring: Hayoto Kurihara, Yukito Hidaka, Yuta Hayashi, Shina Peng, Arazi, Kilala Inori, Pushim, Ayumu Nakajima, Makiko Watanabe, Shiro Sano, Masaru Yahagi, Yousuke Yakamatsu

I return to Event Cinemas George Street and sit down in the middle of Row B in Cinema 3. Row B is my favourite row to sit in most cinemas: I like to sit as close to the screen as possible while still being able to use the armrests of the seat in front of me as footrests (since almost nobody ever sits in Row A). I know most people don’t like to sit so close to the screen because they have to slouch or crane their neck to look up at the screen, but I like looking up at the screen. I like movies to tower over me, looking up at them like I’m staring at the sun or the peak of a mountain or the face of God. I go to the movies to be awed. It’s the only reason, besides impatience, to “go to the movies” instead of waiting 45 days to watch a movie at home on my wide-screen TV.

There’s no one else sitting with me in Row B. The cinema is fuller than it usually would be for a Japanese indie film screening at Event Cinemas George Street — usually it would only screen at one of our Dendy or Palace Cinemas, the city’s two warring arthouse cinema chains — but less full than most nighttime Sydney Film Festival screenings, which are mostly sold out. Maybe it’s because it’s a Wednesday night and only the first day of the festival, so the festival hasn’t built up FOMO buzz yet. Or maybe it’s because this specific movie doesn’t really have any way to market itself?

Happyend is the narrative feature film debut of Neo Sora. The only other movie he’s directed is the concert documentary Ryuichi Sakamoto: Opus, which I heard was good but haven’t gotten around to watching, but even if it was a masterpiece it’s hard to extrapolate whether a good documentary filmmaker will make a good narrative filmmaker — since the quality of a documentary is so dependent on how interesting its subject is, usually moreso than how skilled its director is. And unlike other debut films at the festival it isn’t buoyed by any movie stars, like Michael Shanks Together starring Dave Franco and Alison Brie, or awards buzz, like Hasan Hidi’s The President’s Cake which won the Audience Award and the Caméra d'Or this year at Cannes. I only bought tickets to this movie because I had a few tickets left on my 40-movie Flexipass, after I’d bought tickets to all the movies I really wanted to see, and I decided to take a chance on this because I wanted to support an Asian debut filmmaker and because the vague premise sounded like maybe it could be Minority Report as a highschool deathgame anime? And I love Minority Report and highschool deathgame anime.

So since I’m expecting this movie to be a sci-fi thriller, I’m a little surprised that it doesn’t open with anything exciting or omnious. Instead, it opens on 5 highschool kids27 trying to sneak into a nightclub to watch their favourite DJ. There isn’t even anything notably sci-fi about this scene — the nightclub isn’t populated by aliens or holograms, and looks more like just a shitty bar than the type of thousand $$$ bottle-service nightclubs you usually see in movies — except that the bouncer scans their ID to cross-check it against a public database, instead of having to eyeball whether or not its a fake. Anyway, they sneak in through the back and the DJ starts playing his set…and its a surprisingly great set? It’s such a great set that it makes me realize that most nightclub music in movies is shit, like it’s usually just a repetitive beat loop without any drops or breaks or change-ups? Why is movie nightclub movie so shit?

The music is going HAM and the teenagers are raving in the moshpit, but the camera isn’t matching the energy of the scene with Michael Bayesian flash-cuts or halluciogenic Euphoria spirals. Instead, it remains still and stoic, like a vérité documentary but with the static camerawork of the Ozu and Mizoguchi’s school of Japanese classical cinema. Usually I feel like it’s a flaw if the camera in a party scene isn’t moving with the energy of someone at the party28, but here I think it’s an interesting juxtaposition. This juxtaposition — between the aged, wisened stillness of the style and the youthful, rageful chaos of the story — carries throughout the rest of the movie.

The movie’s “inciting incident” is the 5 teenagers (of the Music Research Club), who sneak back into their school at night to party after the cops shut down the nightclub because the DJ set got too wild, pulling a prank on their principal by flipping his brand new yellow sportscar to balance vertically on its front bumper29. Saying he can “No longer trust you (the students) to know right from wrong,” this incident inspire to install PANOPTY, an experimental AI surveillance system which rewards/deducts points from students based on their behaviour, throughought the school. From there, I’m expecting (or hoped for) Happyend to descend into a sci-fi deathgame dystopia where the students would betray each other to score points before ultimately trying to overthrow their evil machine overlords — climaxing in a violent, and possibly tragic, ending.

But that’s not quite what happens. There is a bit of sci-fi dystopia, but no deathgame and not much more than the present-day would be a sci-fi dystopia to an audience from 10 years ago. There are a few narcs in the grade but the 5 members of the Music Research Club never betray each other, even as they fall out with each other for the normal reasons teenagers fall out with each other, and PANOPTY isn’t portrayed as an evil omniscient AI overlord but as a buggy beta-test that’s more goofy than scary because of how easily its exploited30. The threat of PANOPTY to the students’ right-to-privacy is taken seriously, and their efforts to game/break/overthrow the system provides the narrative spine to the movie’s meandering slice-of-life story, but not any more seriously than the dozen other problems the characters are struggling with as they just try to survive their senior year. There’s a much more dystopian threat lurking in the background of the movie, on news reports that we see on TV and phone screens, in a series of earthquakes of escalating intensity which has led to a rising fear of “The Big One” which the fascist Prime Minister is trying to use to justify invoking his “emergency powers” to initiate martial law in order to crack-down on his political opposition before the upcoming election.

But since this is, at heart, a slice-of-life high school coming-of-age movie — the threat of a possibly apocalyptic earthquake and the rise of a fascist totalitarian police state both take a backseat to the personal problems of its teenage protagonists. The 5 members of the Music Research Club are Yuta, Kou, Ata-chan, Ming, and Tomu. Ming is the only girl in the friend group and considers herself a “perfectly average girl” who has no unique qualities or special talents, and thus she has no idea what she wants to do after graduation. Ata-chan is the genderqueer class clown who likes to make his own clothes and who’s besties with Ming, but who wants to be “more than friends”; and so he’s trying to gather the courage to confess to her and to pursue fashion design as a career instead of just a hobby. Tomu is black and at least partially, and legally, American — he speaks perfect Japanese and he seems to have known the others for several years, so presumably he isn’t an American exchange student but a hafu or his parents relocated to Tokyo for work (possibly as US military?) — and he’s torn between returning to America for college to rediscover his ancestral roots and experience what it’s like to not be a minority31 or staying in Japan and sticking together with his friends. All of the characters in the movie are interesting and well-acted; but Yuta and Kou are the two main characters, and its their relationship that’s the emotional and thematic crux of the movie.

Yuta and Kou are childhood BFFs. They’re “brothers from another mother”. They’re always together that they’re usually referred to as one person or as two halves of a double act — Yuta & Kou — in a way that other characters later call out as toxically codependent. Yuta is the “big brother” of the friendship and the leader/founder of the Music Research Club as the only member of the club who has musical talent, not just musical taste. He dreams of becoming a famous DJ, and he’s charismatic and talented enough to have swept his friends up into his dream: whenever they worry about what they’re going to do after graduation, he tells them to chill out because he’s gonna become a rich and famous musician and then they can all just hang with him for the rest of their lives as his entourage! Kou isn’t much like Yuta: he’s broodingly cool instead of flamboyantly hot, he’s the dependable sidekick instead of suffering from Main Character Syndrome, he grew up poor as a 4th or 5th generation undocumented Zainichi32 instead of upper-middle class Yamato Japanese, and he’s spent his whole life following other people’s dreams — whether its his mother’s dream for him to go to college and become a naturalized Japanese citizen, or Yuta’s dream for them to be an internationally famous DJ duo — that he never bothered to have his own dreams. Until now…

In response to the installation of PANOPTY and the Prime Minister trying to institute martial law, Kou joins the rising progressive protest movement — leading to his political awakening. Or does he just join to hook up with the hot rebel-activist girl who’s the leader of the anti-PANOPTY student protests? Either way, this leads to him drifting away from Yuta as he skips Music Research Club to go to protest marches and Marxist salons with his love interest. They always had contrasting personalities, but now that they also have diverging interests and idealogies — with Kou’s leftist intellectual political activism incompatible with Yuta’s childish-rockstar hedonistic nihilism (his personal philosophy is “The world’s already over! Music peaked in the 90s! Let’s just have fun!”) — what do they have in common besides their past? Late in the movie when Kou asks “Do you think we would’ve become friends if we met today instead of as kids?” Yuta doesn’t have an answer. Is Kou actually in love with the hot activist girl or is he just pursuing her to distance himself for his codependent maybe homoerotic best friendship with Yuta? And in doing so, is he actually striking out by himself and pursuing his own interest, following his own dreams, or is he now just following the hot activist girl’s dreams instead of Yuta’s?

Happyend doesn’t have clear answers to any of these ambiguous character questions, even though it cleanly and satisfyingly wraps up its story with minimal loose plot threads. When I had thought this movie would be a sci-fi deathgame dystopia, I had assumed the title was ironic — but in fact it’s a spoiler. This movie has a happy, if anticlimatic, ending. The “Big One” never hits and the fascist Prime Minister is voted out of office, the students stage a successful non-violent sit in protest which convinces the principal to uninstall PANOPTY on the condition that whoever was responsible for wrecking his car comes forward, and Yuta mends his relationship with Kou by voluntarily taking the fall for their shared crime33 and getting expelled from school — which pisses of his Mum but doesn’t really matter to him since he doesn’t need to graduate since he never planned on going to college anyway since he still plans on becoming a famous DJ. The movie ends on a bookend: in the beginning of the movie, after staying up all night clubbing and flipping the principal’s car, Yuta and Kou walk over an overhead bridge — whose left staircase-exit leads to Yuta’s apartment and right staircase-exit leading to Kou’s house — and after trying to say “goodbye” several times they both decide to go crash at Yuta’s apartment. At the end of the movie, after graduation, they walk across the same overhead bridge…but this time they go their seperate ways, as Kou exits right to meet up with his girlfriend and Yuta exits left to go look at an apartment to rent since he was kicked out by his Mum after getting expelled.

I’m surprised by how surprised I am by Happyend. Usually when a movie is surprising it’s because it’s shocking, with a twist ending or like how the bloody violence in The Phoenician Scheme is shocking for a Wes Anderson movie. But Happyend is surprising in its subtlety, its shockingly anti-climatic without being unsatisfying, it subverts expectations in how it doesn’t subvert expectations: I was expecting this slice-of-life coming-of-age story to twist into a sci-fi deathmatch dystopia, but instead it just stayed a slice-of-life coming-of-age story. Neo Sora is shockingly, impressively restrained for a first-time (narrative) filmmaker. He’s only 34 but he moves his camera — or rather doesn’t move his camera — with the Zen calm of an old master, like Ozu or Koreeda34 or Hamaguchi35. Unlike many first-time filmmakers, he feels no need to prove himself or try to impress anyone with fancy camera moves or “gotcha!” plot twists or scenery-chewing monologues.

Yet this doesn’t feel like an old man movie. It pulses with youthful energy — literally so, with its awesomely operatic electronica soundtrack. Beneath its calm aesthetic runs an undercurrent of urgent, political rage. It’s not the type of “political movie” that Hollywood makes: the Oliver Stone-esque retrospective “I told you so” rant that veers into conspiracy theory, or the Aaron Sorkin neo-liberal propaganda of how “one good man” can single-handedly reform an inherently corrupt system, or the escapist blockbuster fantasies of rebellion ala Star Wars or The Hunger Games. Happyend isn’t a movie about how to save the world or start a violent revolution. Instead, it’s about how to survive revolutionary times — whether that be the rise of fascism or the onset of puberty — while maintaining your dignity and your relationships. Which may not be as exciting as teaching us how to blow up a Death Star, but which will probably be more useful for most of us who aren’t going to become guerilla freedom fighters fighting to overthrow the government.

Grade = S (9.6/10)

(8:15 — 8:30 PM) INTERMISSION

I go to the bathroom in the 15 minutes between Happyend and my next and last movie of the night, It Ends.

(8:30 PM) IT ENDS

Friends on a late-night foor run become trapped on an infinite highway with otherwordly terrors lurking beyond. Confined in their Jeep Cherokee, they must decide whether to accept their fate or attempt escape.

Writer-Director: Alex Ullom

Starring: Michell Cole, Akira Jackson, Noah Toth, Phinehas Yoon

I’m in Cinema 3 again for It Ends, but this time I’m in Row A because Row B was full and this time I don’t have the row to myself. The cinema’s sold out, except for a few scattered seats on the aisle rows. It’s surprising, like Happyend, this is also a genre film by a debut writer-director with no movie stars. Maybe the better turn-out is because of the latter timeslot. Or maybe this has more buzz coming hot out of its SXSW premiere in March. Or maybe it’s because high-concept horror tends to play better than slice-of-life sci-fi as “midnight movies” at film festivals. Or maybe the writer-director Alex Ullom is more famous than I think he is? He has a few short films listed on his IMDB page, so maybe he’s like David F. Sandberg — who posted his horror short films on viral until one of them went viral and was expanded into a feature in Lights Out (2016). But none of the short films on Ullom’s IMDB page are titled It Ends.

It Ends opens with…I forget the characters names so I’m just going to refer to them by their horror movie archetypes. So It Ends open with Military White Guy (Mitchell Cole), Goofy White Guy (Noah Toth), and Black Girl (Akira Jackson) picking up the 4th member of their friend group, Asian Guy (Phinehas Yoon), in Military White Guy’s Jeep Cherokee to go on a roadtrip. As they talk-and-drive, we pick up context clues as to these characters relationships and why they’re on this roadtrip: they’re highschool friends who all went to colleges in the same city, with the exception of Military White Guy who joined the military and has just returned to the city after being discharged, and this roadtrip is both a post-graduation “last hurrah!” and to help Asian Guy move to a new city for work. We also get a decent sketch of their personalities: Military White Guy is the strong, silent, brooding man-of-action (he the driver) type; Asian Guy is a high-achieving corporate drone at work but lets loose as a wisecracking kinda-asshole with his friends; Goofy White Guy is both the class clown and the baby of the group and is in some sort of on-again-off-again relationship with Black Girl, who is a cool artist who had something mysteriously traumatic happen to her last summer that she doesn’t want to talk about. After about 15 minutes of establishing the characters, the twist happens — or not so much the “twist” as the premise of the movie — when they turn onto an empty country highway…and can’t turn off?

Over the next 30 minutes, the characters do what they do in every high-concept horror movie. They spend 15 minutes swinging between shock and denial, yelling “This can’t be happening!” and “We must be dreaming, right?”; and then the next 15 minutes testing the limits of the premise. The road is seemingly endless and they have to keep driving because if they stop the car for longer than 90 seconds they’re swarmed by zombie-like people screaming “LET ME IN!” “HELP US!” “GIVE US A RIDE!” who run out from the trees and try to steal their car. However, they soon realize that they no longer need to eat, drink, sleep, or defecate — so there’s nothing to physically stop them from driving forever. These 30 minutes are the peak of the movie, or are at least the scariest stretch of the movie, with a relatable characters in a simple “what would I do in this situation?” premise and the surrealistic nightmare of being trapped on an endless highway interjected with jumpscares from the zombie-hitchhickers. Which is why I kept wondering if this was a short film that was stretched out into a movie, because it would be a great 45-min short but as a 87-min feature…

Once they establish the “rules” of the endless highway, there are lingering questions (e.g. why are they on the highway? who are the hitchhikers in the forest? what happened to the people from the empty cars on the highway? how do they escape the highway?) but no new twists or escalations. So the highway just becomes an endurance test — but a purely psychological endurance test, since their physical health is inexplicably perfectly sustained. The only threat to their survival becomes…boredom? I understand what this movie is trying to do: hook us with a catchy studio horror premise to rope-a-dope us into an existential horror art film…but it’s very hard to tell a story about boredom which isn’t boring. You can do it in a novel because even when nothing interesting is happening in the plot you can still be entertained by the characters internal monologues (e.g. Stoner by John Williams). You can do it if you have Samuel Beckett’s mastery of dialogue, with Waiting For Godot being an obvious reference point for this movie. But it’s especially hard to do in a movie because movies are inherently about motion — they’re moving pictures — unless you’re a master filmmaker like Chantel Akerman but even her Jeanne Dielman…, which was voted #1 in the latest Sight & Sound poll, ends in a memorably shocking act of violence. From the 45-min to the 70-min marker It Ends is a pretty boring movie, but is that a bug or a feature if it’s deliberately boring to immerse us in the characters emotional state of existential boredom? I’m not sure but it did make me consider leaving the cinema, like the characters were desperately wishing they could leave the highway, but I stuck it out because I’d already invested so much time into it that I needed to know how it ends…like the characters keep driving because they hope that they might be able to get to the end of the road…

As It Ends drives through its final few minutes, I wonder how it could possibly end in a satisfying way. Its premise seems to have written itself into a corner, between a rock and a hard place. If they keep driving but never get to the end of the road (if there even is an end of the road), then the movie won’t have an ending. If they give up on trying to get to the end of the road and just become zombie-hitchhikers in the woods, then the movie might be too depressing. If the actually reach the end of the road and escape, then any moral about how “it’s not about the destination, it’s about the journey” goes out the window. I won’t spoil how It Ends ends, but its a more surprisingly satisfying ending than any I theorized…but falls short of the profundity it’s reaching for which might’ve justified the deliberately boring, overlong 2nd Act.

After the movie, I turn to the man sitting to my left and ask him:

Me: “So what did you think of the movie?”

This is a big deal for me. I rarely have the occasion to meet new people, let alone new people who share my interests. So this Sydney Film Festival, I’ve decided I’m going to try to talk to the people sitting next to me…if they’re also sitting alone and seem like they want to talk. The man on my left looks about my age, maybe a few years ago, and if he strapped on a white beard he could be a pretty convincing mall Santa — he even has the Santa Claus jolly chortle, as he laughed louder than anyone else in the cinema whenever any character made a joke. I decide to talk to him instead of the group of three girls on my right, who came in together and are already all talking to each other.

Jolly Man: “It was…interesting…”

At film festivals, “it was interesting…” is the polite cinephile way of saying “it was boring…”

Jolly Man (cont.): “I was getting bored in the middle.”

Me: “But is that a good or a bad thing, since the movie is about boredom?”

Jolly Man: “Right! I’m not sure? It was more existential horror than horror-horror. Or like Kafka, Beckett, or Borges.”

I’m enough of a reader to know who Franz Kafka, Samuel Beckett, and Jean Louis Borges were; but not enough of a reader to have read anything they’ve written. To avoid the embarassment of revealing that I’m an unintellectual illiterate, I change the subject:

Me: “Do you think it was about COVID?”

Jolly Man: “Hmm?”

Me: “Because of having to deal with the existential boredom of being trapped in a confined space with the same people for an indefinite amount of time?”

Jolly Man: “Oh yeah, maybe? When they introduced it they did say the director came up with the idea in 2021, so that would’ve been right around COVID.”

I have more to say about the movie, but the credits have finished rolling and the lights are up now and the cinema’s half empty and it’s already after 10PM and I’ve got to make my train. So I start walking out of the cinema. Should I have said “goodbye” or “nice talk” to Jolly Man before leaving? I’m not sure when it comes to casual interactions with strangers, like should I say “goodbye” to the cashier after they hand me my food?

Grade = A- (7.7/10)

(10:00 — 11:00 PM) Going Home…

It’s only a few minutes walk from Event Cinema George Street to Town Hall station. From there, I catch the train to Burwood and then catch the bus back to my house. Usually when I go to the city my parents would drop me off at North Strathfield or Concord West station, both of which are closer to my our house than Burwood, but they’re away on vacation in Italy and I haven’t got my P plates yet — I finally got my L plates this year — so I can’t drive myself to the station and back. I forgot their exact vacation schedule, but I think my parents might be flying to Venice or Florence today and I worry about them a little because the plane crashes in The Phoenician Scheme reminded me of how planes have been randomly falling out of the sky all year. On the train I google who the DJ was in Happyend and find out he’s a real-life cult-famous DJ, Yousuke Yukimatsu. I can’t find his music on Spotify, but I find him on Soundcloud — I didn’t know that DJ sets were on Soundcloud (I gues they can’t be on Spotify because of unlicensed samples), which I thought was mostly for bad trap rappers — and listen to his Tokyo Boiler Room set the rest of the way home. I never bothered learning to drive because I rarely have anywhere to go that I can’t get to by public transport, and I figured when I did I could either hitch a ride or grab an UBER, but my grandpa hasn’t been able to drive since he had a stroke last year so I started learning to drive this year so I could help drive my grandparents to the doctor and to the grocery store. I like driving. It can be stressful changing lanes on a motorway, and frustrating when I’m caught in traffic, and although I haven’t had an accident yet it was pretty scary when I turned a corner too tight that I burst my tire. But I feel strangely Zen when I’m moving with the flow of traffic, when the lights turn green exactly as you reach them and you never have to stop and can just keep driving and driving and driving. By the end of It Ends, their Jeep Cherokee’s odometer tells us that the characters have been driving for about 1,200,000 miles. On an open, relatively straight road with no traffic — let’s assume that on average they’re driving about 80mph? That would take them 15,000 hours; which is 625 days, or about 1 year and 8 months. Am I one of those assholes who thinks 100 men could beat a gorilla in a fight if I think I could’ve survived the endless highway of It Ends without going crazy from boredom? I mean, we all survived 2-3 years of on/off COVID locksdowns36 without going crazy from boredom. Sure, during COVID we had the internet to keep us connected and entertained— there’s no reception on the endless highway — but I feel like the characters in It Ends could’ve starved off suicidal boredom if they’d remembered to download more media for their roadtrip. You can fit like 10,000 books on a Kindle.

because an “Opening Day” premiere just doesn’t sound as a fancy.

Together currently has 100% on RottenTomatoes.

as the largest of the 6 cinemas hosting screenings for the festival

It’s about a globalist cabal artificially inflating the price of bashable rivets to prevent “wealthy industrialist” (or criminal middle-man) Zsa-Zsa Korda from completing his “Phoenician Scheme” which…has something to do with a dam?

For new readers unfamiliar with my personal ranking system: that’s a 9/10 to an 11/10.

Asteroid City is currently my 47th Favourite Movie Ever, between 21 Jump Street and Madame Web.

I bought Asteroid City on Blu-Ray and have now watched it 4 times.

Okay, fine, 20 minutes.

because I’d been up until 3AM booking my tickets to the Sydney Film Festival.

who shares Zsa-Zsa’s nickname “Mr. Five Percent” for his signature of taking a 5% share of any deal he helps negotiate.

where the movie was filmed in Studio Babelsberg in Potsdam.

and told linearly, without the complex chaptered meta-narratives of Wes Anderson’s last few films: The Grand Budapest Hotel, The French Dispatch, and Asteroid City.

a remake of his own A Story of Floating Weeds (1934).

The English-language remake of his 1997 Austrian original of the same name.

and the greater absurdism of how he becomes weirdly sexy just by dropping his accent and turning up his jacket collar?? IS MICHAEL CERA HOT ACTUALLY WERE THE LATE 2000s RIGHT TO CAST HIM IN ALL THE TEEN ROMCOMS???

This one might be a bit confusing out-of-context, but trust me it’s hilarious in the context of the movie!

It’s my 7th favourite of Wes Anderson’s 12 feature films (so far): below Asteroid City, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Rushmore, Moonrise Kingdom, Fantastic Mr. Fox, and Isle of Dogs; and above The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou, The French Dispatch, Bottle Rocket, The Darjeeling Limited, and The Royal Tennenbaums.

even if The Phoenician Scheme is unlikely to be anyone’s favourite Wes Anderson movie — it might make for his best coffee table artbook!

e.g. Pain and Glory — which is a great movie, but part of the somewhat tiring trend of master filmmakers making childhood memoirs.

e.g. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood… — which is a great movie, but isn’t about anything besides movies…which I don’t mind since I don’t know anything besides movies.

which was a real disease, to be clear!

and it still is.

It’s set in 1950s Nuclear Age Americana and interrogates toxic masculinity, like Oppenheimer tries (but fails), but with the with Barbie’s whipsmart comedy and dollhouse production design.

and has several other plane crashes throughout the movie.

who joined the Wes Anderson ensemble in his Roald Dahl short The Ratcatcher (2023) and plays a supporting role as Sergio, the leader of a terrorist/freedom-fighter jungle militia, in The Phoenician Scheme.

which everywhere else in the world is known as Burger King.

They’re instantly recognisable as highschool kids because they’re all still dressed in their generic Japanese highschool uniforms. Why didn’t they change out of their uniforms if they’re trying to sneak into a club? I guess they came straight from school?

e.g. I am in the minority of being underwhelmed by this scene in Sinners.

The movie never explains how these kids did this. Does anyone know how to do this? Do these kids have superstrength, or are they physics geniuses, or do they have access to a tow truck?

The funniest gag in the movie is when Yuta and Kou, the main characters, stand in one of PANOTY’s blindspots and when the narc captain of the baseball team runs by and yells at them to stop smoking; they throw the cigarettes at his feet and when the baseball captain picks it up to throw it in the rubbish (because he doesn’t want them litterring) PANOTY thinks that the baseball captain is smoking the cigarette and deducts -100 points.

even though he understands that as a black person in the USA he’d still be a minority and have to deal with a whole different type of racism than the “exoticism” he has to deal with as one of few black people living in Japan.

Ethnic Koreans who migrated to Japan before or during WW2 and their descendents, many of whom are still undocumented despite their families having now lived in Japan for generations.

It was only Yuta and Kou that pulled off the car prank — the other 3 members of the Music Research Club weren’t involved, although they were aware.

“we” as in me and everyone who’s alive to read this, because obviously not everyone survived COVID